Why India needs to protect its small dairy farmers

The ongoing negotiations under the RCEP for reducing or rationalising import duty structure by India would open a floodgate for dumping of cheaper dairy products from Australia or New Zealand, which would hit millions of Indian dairy farmers.

In the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), many participating developed countries like New Zealand and Australia have been urging India to open up the dairy sector through reduction of import duties. At the 8th RCEP (a formidable trade block of 16 countries, including India) meeting of the intersessional ministerial held in Beijing last month, trade negotiators focused on two aspects. While New Zealand demands greater market access for its dairy products, apples, kiwis and wine into India, India has been demanding greater access of professionals into New Zealand and easing the market barrier that it imposes.

The Indian dairy industry says that import concessions on dairy products from milk-surplus member countries like New Zealand and Australia will have an adverse impact on India’s dairy sector. This might impact around 100 million dairy farmers and people associated with the sector in the country.

In the 1950s, India was a milk-deficit country, depending largely on imports. Launched in 1970s, the three-phase Operation Flood helped the country’s milk production soar, providing livelihoods to millions of farmers through the cooperative model. And because of the success of the Operation Flood, brands like Amul (Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation), Nandini (Karnataka Milk Federation), Milma (Kerala Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation) and Verka (Punjab State Cooperative Federation of Milk Producers Unions) became household names.

By 1998, India overtook the US to become the largest milk producer in the world. India continues to be the largest milk producer with a production of 176 million metric tonnes in 2018-19. The country’s dairy sector, the largest among agricultural commodities, is estimated to have a value of $100 billion and constitutes 20% of the total global milk production. According to International Farm Comparison Network (IFCN, 2018), this value is expected to double and will account for more than 30% of the world’s milk production by 2033. As per a NITI Aayog Working Group report, the total demand of milk during 2033-34 would be around 292 million metric tonnes, as against supply of around 330 million metric tonnes.

Of India’s 100-million-plus dairy farmers, more than 70 million hold 2-3 milch animals per head. RCEP negotiations are crucial to the survival of India’s dairy sector as milk production in India is smallholder-centric. Moreover, the Indian dairy sector employs millions of people on an annual basis, of which more than 70% are women and 69% belong to socio-economically deprived sections of the communities.

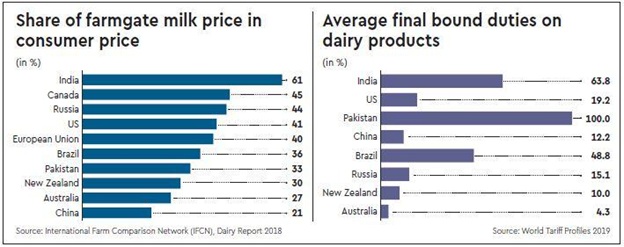

An Indian dairy producer in the organised sector receives more than 60% share of the consumer rupee as against 30% for a New Zealand-based producer. According to the IFCN (2018), in Australia and the EU, the farmers’ receipt is 27% and 40% of the consumer’s rupee spent, respectively (see table). Today, India is self-sufficient in milk, having surplus trade balance in dairy. Moreover, the production would grow, leaving substantial market surplus in the future.

According to the IFCN (2018) report, places like New Zealand, Australia, the EU and the US have milk self-sufficiency of more than 800%, 117%, 111% and 105%, respectively. It is, thus, natural that these countries would look for market push in countries they could manage through the RCEP.

At this juncture, we must learn from China, a country that is demographically similar to India. China’s CAGR in dairy dropped from 22% (2000-06) to 0.06% (2006-17), leading to increased dependency on imports. Post-FTA, China’s dairy imports increased from 3.5% to 20% by 2017. Even back home, in the case of edible oil, the entire industry has moved from self-sufficiency to import dependency post the WTO implementation in 1996-97.

According to industry estimates, the market share of Indian dairy products comprising of skimmed milk powder, butter and cheese is estimated to be around 0.5 million metric tonnes. If we allow imports, say, from New Zealand, across all value-added dairy products equivalent to 5% of their total exports in each of the above product category, it will be around 0.133 million metric tonnes. In this scenario, New Zealand alone will capture almost one-third of the market of domestic players in India, who are instrumental in procuring milk from a huge number of dairy farmers of the country. This will have an untimely impact on the organised dairy sector, which has been improving slowly but steadily over the past few years. Indian farmers are getting better returns compared to other dairy-developed countries like New Zealand, Australia and the US. In the current scenario, import tariffs on value-added dairy products are around 64%, which helps protect the domestic dairy industry as well as the interest of small and marginal farmers (see table).

Income centrality of small and marginal farmers in India is towards dairying. We must learn from the strategic positions every country takes for allowing imports on dairy products. For example, Canada imposes a duty of 208% on all dairy products. The EU promotes non-tariff barriers with high residual and pesticides limits. Australia does not permit non-retorted dairy products from India. Countries like South Africa, Mexico, Venezuela and Chile do not permit import of dairy products from India.

According to the World Tariff Profiles (2017) of the WTO, Pakistan imposes 100% protection on its dairy products, which is the highest amongst the milk-producing countries, followed by India (64%), Brazil (49%) and Australia (4%), which is the lowest protection amongst the milk-producing countries.

The Make in India policy is the most amenable to its dairy producers and processor companies who mostly use locally-available resources. Most of the resources are available as India continues to have a healthy growth in foodgrains and other crop production. For achieving the government’s aim of doubling farmers’ incomes by 2022-23, India needs to protect the interest of its small, marginal and landless dairy farmers.

Source : financialexpress